Hope From Heartache, Franklin Center at Bricks

May 24, 2023

I spent this weekend in community with folks I’ve only known on Zoom for the last 2 years. You’ve probably heard me mention Alternate ROOTS, an arts service organization based in the Southern USA. It’s a coalition of cultural workers who strive to eliminate all forms of oppression. I joined two years ago and have served on the Executive Committee for the last year.

We sang, danced, did yoga, slept, made crafts, told stories, stayed up late, laughed, ate so well, played outside, walked, and meditated. And all of it was centered around self-care, community care, and social justice. I showed up a little nervous and excited. I left happy, satisfied, feeling connected, (and of course, tired – ha ha).

I was nervous about going because I was meeting most of the people for the first time and because I knew the Franklin Center at Bricks, where we were staying, was a former plantation. As an empath, I was concerned about what I might feel staying on the land. But as I drove onto the property, the trees extended a hello and told me that I was safe and welcome. The first person I met, Interim Executive Director Elly Mendez Angulo Brown, was a whirlwind of activity and love and put me at ease.

Once I brought my belongings into the building, the trees called me back outside, so I kicked off my shoes and walked across the property to the ones I heard the loudest and I stood with them and listened. I tried to walk away as I saw people I recognized arriving, but one tree in particular wouldn’t let me walk away until I ducked under its branches to lean against its trunk to not only feel grounded through my feet, but also connect at my heart.

One of the first trees to greet me

I debated whether to learn more about the history of the property right away. I didn’t want historical facts to shift my feeling of oneness. So I enjoyed my friends and the food and the work. As we learned about the history, I was so grateful to be outside. I kicked off my shoes and dug my feet into the grass as we listened to Elly’s masterful telling of the history of the land.

The land was originally stewarded by the Cherokee, Coharie, Haliwa-Saponi, and Lumbee. The Tuscarora Nation of North Carolina, comprised of autonomous bands who act together as one nation, outlines their history from the 1500s through the present.

During slavery, the 1,000 acres was used as a breaking plantation – where they sent enslaved folks who had the audacity to believe they should be free so that belief could be beaten out of them. I listened and breathed deeply and dug in my feet. I wondered, how I was feeling safe in a space with this history?

Interim Executive Director Elly Mendez Angulo Brown

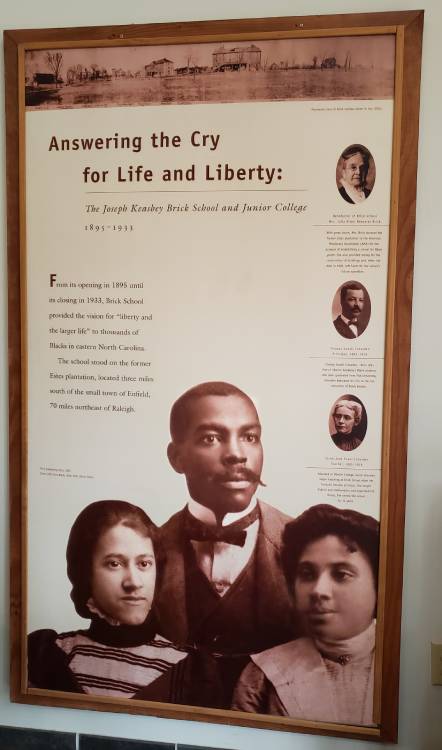

But then Elly started talking about the Reconstruction Era, true allyship, and Black determination. Mrs. Julia Elmer Brewster Brick, a white woman with inherited family wealth (from the Brewsters of New York and her deceased husband Joseph Keasbey Brick) owned the land. She donated the former Estes Plantation to the American Missionary Association, who were experts at establishing Black schools. Mrs. Brewster Bricks required that the school:

- be used for the education of those coming out of the history of enslavement

- bear her husband’s name

- have a lasting legacy

The Joseph Keasbey Brick Agricultural, Industrial and Normal School was one of the few accredited private schools for Black youth. Mrs. Brewster Brick provided money for the construction of buildings, and when she died in 1903, she left funds for the school’s future operation.

Wall panel featuring Mrs. Julia Elmer Brewster Brick, Mr. Thomas Sewell Inborden, and Mrs. Sarah Jane Evans Inborden

Mr. Thomas Sewell Inborden, a student of Oberlin University who graduated from Fisk University, dedicated his life to the full education of Black people and was the principal from 1895 until 1926. His wife, Sarah Jane Evans Inborden taught English and math and organized the library, serving the school for 31 years.

Listening to the story of how Mr. Inborden slept on the land as the school was being built, advocated for the children to have what they needed, had 13 children sleeping in a space designed for 2 because the school didn’t want to turn kids away just reminds me how much Black folks have traditionally valued education.

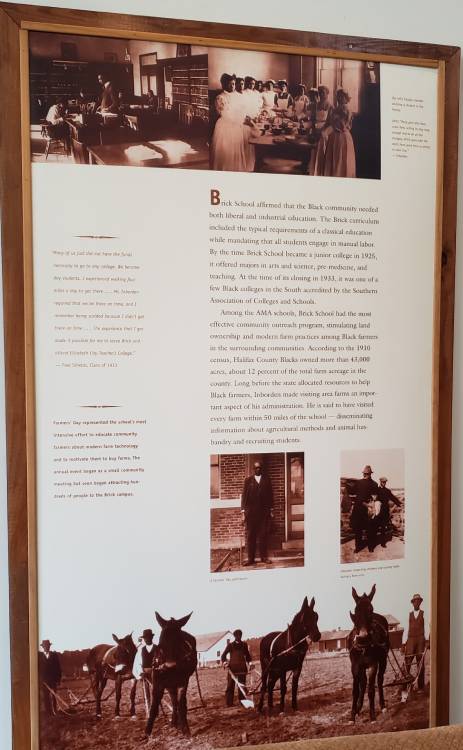

Students received a classical education and were required to do manual labor. Notice how they are dressed, working the land in dress clothes. I’m sure you’ve heard the saying that Black folks have to be twice as good to get half as far. These students were held to that standard.

Wall panel about classical education and manual labor, featuring photos of students

In 1925 when the school became the Joseph Keasbey Brick Junior College, the school offered majors in teaching, arts and science, and pre-medicine.

Three structures from the original campus are still standing – two houses where teachers lived on campus and the oldest usable space is the original dining hall, which is now part of the administrative building.

The center of the administration building was the original dining hall. The two wings were added later.

The school did major community outreach, with Mr. Inborden visiting farms within a 50-mile radius to disseminate information about agricultural methods and animal husbandry as well as to recruit students.

In 1933, during the Great Depression, the school closed.

In 1946 The Franklin Center was formed to provide opportunities for Christian education and fellowship, and in 1954, the center moved to Bricks. It was renamed the Franklin Center at Bricks in 1994 as a ministry of the United Church of Christ. It became a stand-alone nonprofit in 2015 and continues the traditions of the school with gardening and food distribution for the community, educational opportunities, and community outreach, along with a conference center for social justice.

After hearing all this history (and I don’t have space to put it all here), I was left with so much hope! What I thought about was how the land was respected from the beginning. Then there was a period where the land and people were devastatingly mistreated. Then the people who were enslaved and beaten created something powerful and binding and centered in community care. And it didn’t take thousands of years or millions of people to make the change. And the land has been healed. You can feel it. It’s not haunted. It’s not angry. The location is full of love and acceptance.

And if a place that was used to break people of their desire for freedom can become a place of rest, healing, and celebration, then there’s hope for community-building and safety in the most hateful, small-minded communities we know of today.

The Franklin Center at Bricks is the personification of the Margaret Mead quote, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.”

Ready to DO something right now? Download the Everyday Activism Action Pack and get started today.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information for any reason.